09.12.2022

“Egyptian Nights” is an unfinished story by Alexander Pushkin, published after his death in the Sovremennik magazine.

The Egyptian Nights – read online

CHAPTER I

CHARSKY was one of the native-born inhabitants of St. Petersburg. He was not yet thirty years of age; he was not married; the service did not oppress him too heavily. His late uncle, having been a vice-governor in the good old times, had left him a respectable estate. His life was a very agreeable one, but he had the misfortune to write and print verses. In the journals he was called “poet,” and in the ante-rooms “author.”

In spite of the great privileges which verse-makers enjoy (we must confess that, except the right of using the accusative instead of the genitive, and other so-called poetical licenses of a similar kind, we fail to see what are the particular privileges of Russian poets), in spite of their every possible privilege, these persons are compelled to endure a great deal of unpleasantness. The bitterest misfortune of all, the most intolerable for the poet, is the appellation with which he is branded, and which will always cling to him. The public look upon him as their own property; in their opinion, he was created for their especial benefit and pleasure. Should he return from the country, the first person who meets him accosts him with:

“Haven’t you brought anything new for us?”

Should the derangement of his affairs, or the illness of some being dear to him, cause him to become lost in thoughtful reflection, immediately a trite smile accompanies the trite exclamation:

“No doubt he is composing something!”

Should he happen to fall in love, his beauty purchases an album at the English warehouse, and expects an elegy.

Should he call upon a man whom he hardly knows, to talk about serious matters of business, the latter quickly calls his son and compels him to read some of the verses of so-and-so, and the lad regales the poet with some of his lame productions. And these are but the flowers of the calling; what then must be the fruits! Charsky acknowledged that the compliments, the questions, the albums, and the little boys bored him to such an extent, that he was constantly compelled to restrain himself from committing some act of rudeness.

Charsky used every possible endeavour to rid himself of the intolerable appellation. He avoided the society of his literary brethren, and preferred to them the men of the world, even the most shallow-minded: but that did not help him. His conversation was of the most commonplace character, and never turned upon literature. In his dress he always observed the very latest fashion, with the timidity and superstition of a young Moscovite arriving in St. Petersburg for the first time in his life. In his study, furnished like a lady’s bedroom, nothing recalled the writer; no books littered the table; the divan was not stained with ink; there was none of that disorder which denotes the presence of the Muse and the absence of broom and brush. Charsky was in despair if any of his worldly friends found him with a pen in his hand. It is difficult to believe to what trifles a man, otherwise endowed with talent and soul, can descend. At one time he pretended to be a passionate lover of horses, at another a desperate gambler, and at another a refined gourmet, although he was never able to distinguish the mountain breed from the Arab, could never remember the trump cards, and in secret preferred a baked potato to all the inventions of the French cuisine. He led a life of unbounded pleasure, was seen at all the balls, gormandized at all the diplomatic dinners, and appeared at all the soirees as inevitably as the Rezan ices. For all that, he was a poet, and his passion was invincible. When he found the “silly fit” (thus he called the inspiration) coming upon him, Charsky would shut himself up in his study, and write from morning till late into the night. He confessed to his genuine friends that only then did he know what real happiness was. The rest of his time he strolled about, dissembled, and was assailed at every step by the eternal question:

“Haven’t you written anything new?”

One morning, Charsky felt that happy disposition of soul, when the illusions are represented in their brightest colours, when vivid, unexpected words present themselves for the incarnation of one’s visions, when verses flow easily from the pen, and sonorous rhythms fly to meet harmonious thoughts. Charsky was mentally plunged into a sweet oblivion . . . and the world, and the trifles of the world, and his own particular whims no longer existed for him. He was writing verses.

Suddenly the door of his study creaked, and the unknown head of a man appeared. Charsky gave a sudden start and frowned.

“Who is there?” he asked with vexation, inwardly cursing his servants, who were never in the ante-room when they were wanted.

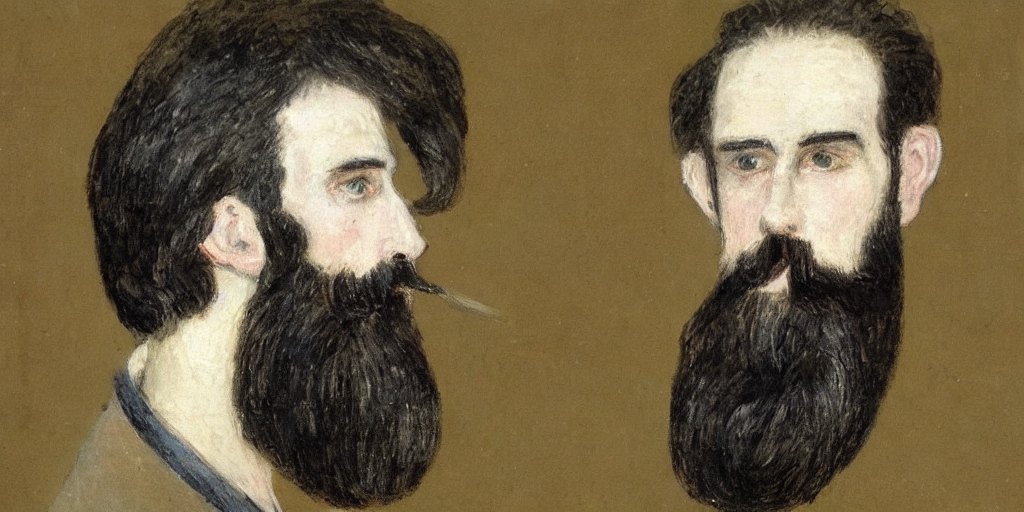

The unknown entered. He was of a tall, spare figure, and appeared to be about thirty years of age. The features of his swarthy face were very expressive: his pale, lofty forehead, shaded by dark locks of hair, his black, sparkling eyes, aquiline nose, and thick beard surrounding his sunken, tawny cheeks, indicated him to be a foreigner. He was attired in a black dress-coat, already whitened at the seams, and summer trousers (although the season was well into the autumn); under his tattered black cravat, upon a yellowish shirt-front, glittered a false diamond; his shaggy hat seemed to have seen rain and bad weather. Meeting such a man in a wood, you would have taken him for a robber; in society—for a political conspirator; in an ante-room—for a charlatan, a seller of elixirs and arsenic.

“What do you want?” Charsky asked him in French.

“Signor,” replied the foreigner in Italian, with several profound bows: “Lei voglia perdonar mi, si . . .” (Please pardon me, if . .)

Charsky did not offer him a chair, and he rose himself: the conversation was continued in Italian.

“I am a Neapolitan artist,” said the unknown: “circumstances compelled me to leave my native land; I have come to Russia, trusting to my talent.”

Charsky thought that the Italian was preparing to give some violoncello concerts and was disposing of his tickets from house to house. He was just about to give him twenty-five roubles in order to get rid of him as quickly as possible, but the unknown added:

“I hope, signor, that you will give a friendly support to your confrère, and introduce me into the houses to which you have access.”

It was impossible to offer a greater affront to Charsky’s vanity. He glanced haughtily at the individual who called himself his confrère.

“Allow me to ask, what are you, and for whom do you take me?” he said, with difficulty restraining his indignation.

The Neapolitan observed his vexation.

“Signor,” he replied, stammering: “Ho creduto . . . ho seniito . . . la vostra Eccelenza . . . mi perdonera . . .” (I believed . . . I felt . . . Your Excellency . . . will pardon me. . . .)

“What do you want?” repeated Charsky drily.

“I have heard a great deal of your wonderful talent; I am sure that the gentlemen of this place esteem it an honour to extend every possible protection to such an excellent poet,” replied the Italian: “and that is why I have ventured to present myself to you. . . .”

“You are mistaken, signor,” interrupted Charsky. “The calling of poet does not exist among us. Our poets do not solicit the protection of gentlemen; our poets are gentlemen themselves, and if our Mæcenases (devil take them!) do not know that, so much the worse for them. Among us there are no ragged abbés, whom a musician would take out of the streets to compose a libretto. Among us, poets do not go on foot from house to house, begging for help. Moreover, they must have been joking, when they told you that I was a great poet. It is true that I once wrote some wretched epigrams, but thank God, I haven’t anything in common with messieurs les poètes, and do not wish to have.”

The poor Italian became confused. He looked around him. The pictures, marble statues, bronzes, and the costly baubles on Gothic what-nots, struck him. He understood that between the haughty dandy, standing before him in a tufted brocaded cap, gold-embroidered nankeen dressing-gown and Turkish sash,—and himself, a poor wandering artist, in tattered cravat and shabby dress-coat—there was nothing in common. He stammered out some unintelligible excuses, bowed, and wished to retire. His pitiable appearance touched Charsky, who, in spite of the defects in his character, had a good and noble heart. He felt ashamed of his irritated vanity.

“Where are you going?” he said to the Italian. “Wait . . . I was compelled to decline an unmerited title and confess to you that I was not a poet. Now let us speak about your business. I am ready to serve you, if it be in my power to do so. Are you a musician?”

“No, Eccelenza,” replied the Italian; “I am a poor improvisatore.”

“An improvisatore!” cried Charsky, feeling all the cruelty of his reception. “Why didn’t you say sooner that you were an improvisatore?”

And Charsky grasped his hand with a feeling of sincere regret.

His friendly manner encouraged the Italian. He spoke haively of his plans. His exterior was not deceptive. He was in need of money, and he hoped somehow in Russia to improve his domestic circumstances. Charsky listened to him with attention.

“I hope,” said he to the poor artist, “that you will have success; society here has never heard an improvisatore. Curiosity will be awakened. It is true that the Italian language is not in use among us; you will not be understood, but that will be no great misfortune; the chief thing is that you should be in the fashion.”

“But if nobody among you understands Italian,” said the improvisatore, becoming thoughtful, “who will come to hear me?”

“Have no fear about that—they will come: some out of curiosity, others to pass away the evening somehow or other, others to show that they understand Italian. I repeat, it is only necessary that you should be in the fashion, and you will be in the fashion—I give you my hand upon it.”

Charsky dismissed the improvisatore very cordially, after having taken his address, and the same evening he set to work to do what he could for him.

CHAPTER II

THE next day, in the dark and dirty corridor of a tavern, Charsky discovered the number 35. He stopped at the door and knocked. It was opened by the Italian of the day before.

“Victory!” said Charsky to him: “your affairs are in a good way. The Princess N——, offers you her salon; yesterday, at the rout, I succeeded in enlisting the half of St. Petersburg; get your tickets and announcements printed. If I cannot guarantee a triumph for you, I’ll answer for it that you will at least be a gainer in pocket. . . .”

“And that is the chief thing,” cried the Italian, manifesting his delight in a series of gestures that were characteristic of his southern origin. “I knew that you would help me. Corpo di Bacco! You are a poet like myself, and there is no denying that poets are excellent fellows! How can I show my gratitude to you? Stop. . . . Would you like to hear an improvisation?”

“An improvisation! . . . Can you then do without public, without music, and without sounds of applause?”

“And where could I find a better public? You are a poet: you understand me better than they, and your quiet approbation will be dearer to me than whole storms of applause. … Sit down somewhere and give me a theme.”

“Here is your theme, then,” said Charsky to him: “the poet himself should choose the subject of his songs; the crowd has not the right to direct his inspirations.”

The eyes of the Italian sparkled: he tried a few chords, raised his head proudly, and passionate verses—the expression of instantaneous sentiment—fell in cadence from his lips…

The Italian ceased. . . . Charsky remained silent, filled with delight and astonishment.

“Well?” asked the improvisatore.

Charsky seized his hand and pressed it firmly.

“Well?” asked the improvisatore.

“Wonderful!” replied the poet. “The idea of another has scarcely reached your ears, and already it has become your own, as if you had nursed, fondled and developed it for a long time. And so for you there exists neither difficulty nor discouragement, nor that uneasiness which precedes inspiration? Wonderful, wonderful!”

The improvisatore replied: “Each talent is inexplicable. How does the sculptor see, in a block of Carrara marble, the hidden Jupiter, and how does he bring it to light with hammer and chisel by chipping off its envelope? Why does the idea issue from the poet’s head already equipped with four rhymes, and arranged in measured and harmonious feet? Nobody, except the improvisatore himself, can understand that rapid impression, that narrow link between inspiration proper and a strange exterior will; I myself would try in vain to explain it. But . . . I must think of my first evening. What do you think? What price could I charge for the tickets, so that the public may not be too exacting, and so that, at the same time, I may not be out of pocket myself? They say that La Signora Catalani [A celebrated Italian vocalist, whose singing created an unprecedented sensation in the principal European capitals during the first quarter of the present century] took twenty-five roubles. That is a good price. . . .”

It was very disagreeable to Charsky to fall suddenly from the heights of poesy down to the bookkeeper’s desk, but he understood very well the necessities of this world, and he assisted the Italian in his mercantile calculations. The improvisatore, during this part of the business, exhibited such savage greed, such an artless love of gain, that he disgusted Charsky, who hastened to take leave of him, so that he might not lose altogether the feeling of ecstasy awakened within him by the brilliant improvisation. The Italian, absorbed in his calculations, did not observe this change, and he conducted Charsky into the corridor and out to the steps, with profound bows and assurances of eternal gratitude.

CHAPTER III

THE salon of Princess N—— had been placed at the disposal of the improvisatore; a platform had been erected, and the chairs were arranged in twelve rows. On the appointed day, at seven o’clock in the evening, the room was illuminated; at the door, before a small table, to sell and receive tickets, sat a long-nosed old woman, in a grey cap with broken feathers, and with rings on all her fingers. Near the steps stood gendarmes.

The public began to assemble. Charsky was one of the first to arrive. He had contributed greatly to the success of the representation, and wished to see the improvisatore, in order to know if he was satisfied with everything. He found the Italian in a side room, observing his watch with impatience. The improvisatore was attired in a theatrical costume. He was dressed in black from head to foot. The lace collar of his shirt was thrown back; his naked neck, by its strange whiteness, offered a striking contrast to his thick black beard; his hair was brought forward, and overshadowed his forehead and eyebrows.

All this was not very gratifying to Charsky, who did not care to see a poet in the dress of a wandering juggler. After a short conversation, he returned to the salon, which was becoming more and more crowded. Soon all the rows of seats were occupied by brilliantly-dressed ladies: the gentlemen stood crowded round the sides of the platform, along the walls, and behind the chairs at the back; the musicians, with their music-stands, occupied two sides of the platform. In the middle, upon a table, stood a porcelain vase.

The audience was a large one. Everybody awaited the commencement with impatience. At last, at half-past seven o’clock, the musicians made a stir, prepared their bows, and played the overture from “Tancredi.” All took their places and became silent. The last sounds of the overture ceased. . . . The improvisatore, welcomed by the deafening applause which rose from every side, advanced with profound bows to the very edge of the platform.

Charsky waited with uneasiness to see what would be the first impression produced, but he perceived that the costume, which had seemed to him so unbecoming, did not produce the same effect upon the audience; even Charsky himself found nothing ridiculous in the Italian, when he saw him upon the platform, with his pale face brightly illuminated by a multitude of lamps and candles. The applause subsided; the sound of voices ceased . . .

The Italian, expressing himself in bad French, requested the gentlemen present to indicate some themes, by writing them upon separate pieces of paper. At this unexpected invitation, all looked at one another in silence, and nobody made reply. The Italian, after waiting a little while, repeated his request in a timid and humble voice. Charsky was standing right under the platform; a feeling of uneasiness took possession of him; he had a presentiment that the business would not be able to go on without him, and that he would be compelled to write his theme. Indeed, several ladies turned their faces towards him and began to pronounce his name, at first in a low tone, then louder and louder. Hearing his name, the improvisatore sought him with his eyes, and perceiving him at his feet, he handed him a pencil and a piece of paper with a friendly smile. To play a rôle in this comedy seemed very disagreeable to Charsky, but there was no help for it: he took the pencil and paper from the hands of the Italian and wrote some words. The Italian, taking the vase from the table, descended from the platform and presented it to Charsky, who deposited within it his theme. His example produced an effect: two journalists, in their quality as literary men, considered it incumbent upon them to write each his theme; the secretary of the Neapolitan embassy, and a young man recently returned from a journey to Florence, placed in the urn their folded papers. At last, a very plain-looking girl, at the command of her mother, with tears in her eyes, wrote a few lines in Italian and, blushing to the ears, gave them to the improvisatore, the ladies in the meantime regarding her in silence, with a scarcely perceptible smile. Returning to the platform, the improvisatore placed the urn upon the table, and began to take out the papers one after the other, reading each aloud:

“La famiglia del Cenci. . . . L’ultimo giorno di Pompeia. . . Cleopatra e i suoi amanti. . . . La primavera veduta da una prigione. . . . Il trionfo di Tasso.”

“What does the honourable company command?” asked the Italian humbly. “Will it indicate itself one of the subjects proposed, or let the matter be decided by lot?”

“By lot!” said a voice in the crowd. . . . “By lot, by lot!” repeated the audience.

The improvisatore again descended from the platform, holding the urn in his hands, and casting an imploring glance along the first row of chairs, asked:

“Who will be kind enough to draw out the theme?”

Not one of the brilliant ladies, who were sitting there, stirred. The improvisatore, not accustomed to Northern indifference, seemed greatly disconcerted. . . . Suddenly he perceived on one side of the room a small white-gloved hand held up: he turned quickly and advanced towards a tall young beauty, seated at the end of the second row. She rose without the slightest confusion, and, with the greatest simplicity in the world, plunged her aristocratic hand into the urn and drew out a roll of paper.

“Will you please unfold it and read,” said the improvisatore to her.

The young lady unrolled the paper and read aloud:

“Cleopatra e i suoi amanti.”

These words were uttered in a gentle voice, but such a deep silence reigned in the room, that everybody heard them. The improvisatore bowed profoundly to the young lady, with an air of the deepest gratitude, and returned to his platform.

“Gentlemen,” said he, turning to the audience: “the lot has indicated as the subject of improvisation: ‘Cleopatra and her lovers.’ I humbly request the person who has chosen this theme, to explain to me his idea: what lovers is it here a question of, perchè la grande regina haveva molto?”

At these words, several gentlemen burst out laughing. The improvisatore became somewhat confused.

“I should like to know,” he continued, “to what historical feature does the person, who has chosen this theme, allude? . . . I should feel very grateful if he would kindly explain.”

Nobody hastened to reply. Several ladies directed their glances towards the plain-looking girl who had written a theme at the command of her mother. The poor girl observed this hostile attention, and became so confused, that the tears came into her eyes. . . . Charsky could not endure this, and turning to the improvisatore, he said to him in Italian:

“It was I who proposed the theme. I had in view a passage in Aurelius Victor, who speaks as if Cleopatra used to name death as the price of her love, and yet there were found adorers whom such a condition neither frightened nor repelled. It seems to me, however, that the subject is somewhat difficult. . . . Could you not choose another?”

But the improvisatore already felt the approach of the god. . . . He gave a sign to the musicians to play. His face became terribly pale; he trembled as if in a fever ; his eyes sparkled with a strange fire; he raised with his hand his dark hair, wiped with his handkerchief his lofty forehead, covered with beads of perspiration. . . . then suddenly stepped forward and folded his arms across his breast. . . . the musicians ceased. . . . the improvisation began:

“The palace glitters; the songs of the choir

Echo the sounds of the flute and lyre;

With voice and glance the stately Queen

Gives animation to the festive scene,

And eyes are turned to her throne above.

And hearts beat wildly with ardent love.

But suddenly that brow so proud

Is shadowed with a gloomy cloud,

And slowly on her heaving breast,

Her pensive head sinks down to rest.

The music ceases, hushed is each breath,

Upon the feast falls the lull of death;”