06.01.2023

The Russian Military Historical Society has repeatedly addressed the poet’s life and work. Today we will continue this story. It is known that the poet had a difficult relationship with the authorities.

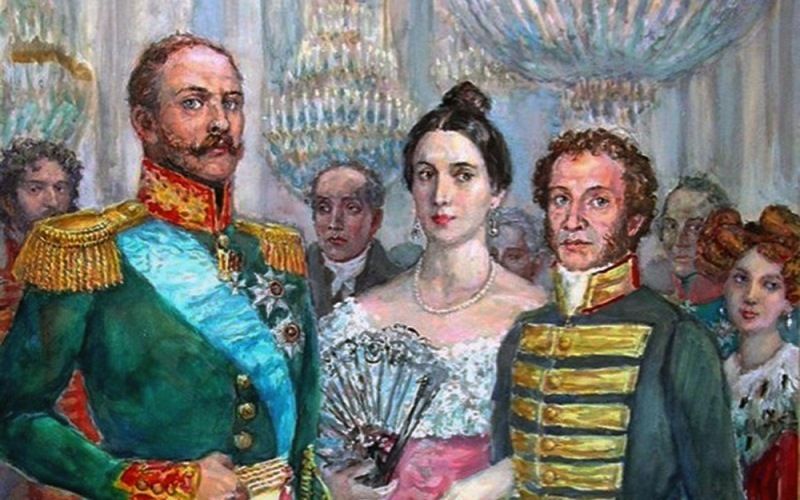

Once, in his letter to his wife Natalia Nikolaevna, Pushkin joked that he had seen three tsars: Paul I, Alexander I and Nicholas I. He said that he saw Paul I as a child: the tsar took off his cap and scolded his nurse for him. Alexander I did not like him at all, but he even had friendly relations with Nicholas I, which lasted until the poet’s death.

The Emperor Nicholas and the poet were almost the same age. They grew up and were brought up at the same time, in the same atmosphere, and even the Decembrist uprising in 1825 connected them in many ways.

Soviet historiography made its own adjustments to the image of the tsar, they say, “Nikolai Palkin”, a tyrant and tyrant, mercilessly persecuted the national genius, and in general it was his fault in the death of the poet.

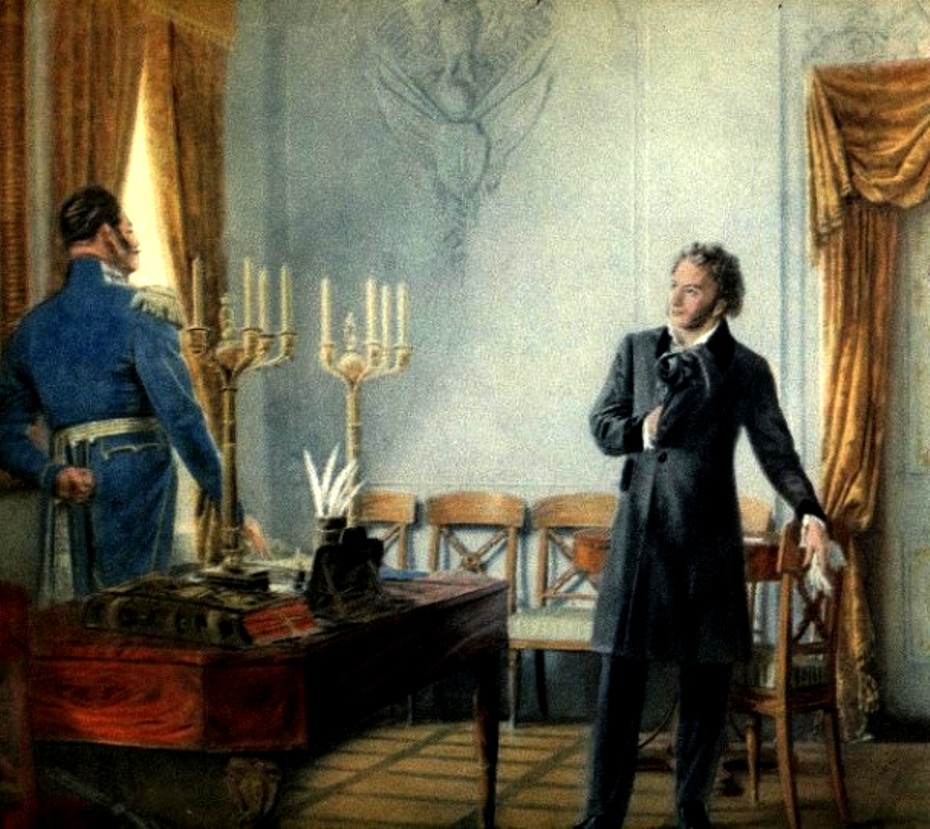

First meeting

Nevertheless, in fact, Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich played an important role in the poet’s life. You remember that Pushkin was considered a “free thinker” in the time of Alexander I. This opinion was not formed from scratch. The whole Russian society in those years literally breathed “free-thinking” and Alexander Sergeyevich simply could not be aloof from these trends. An example is even the fact that at the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum Pushkin’s teacher was the brother of the French “friend of the people” Marat. And many of Pushkin’s friends became Decembrists.

As you know, Pushkin survived the uprising on Senate Square in December 1825 in Mikhailovsky, where he was sent by order of Alexander I. Pushkin could not help but note the courageous behavior of the new emperor Nicholas on the day of the rebellion, and he addressed him with a letter. The emperor released the poet from punishment, allowed him to live freely in the capitals and even set an audience date.

The first meeting took place at the Miracle Palace in Moscow on September 8, 1826. A date with the emperor turned the whole worldview of the 27-year-old Pushkin. He came to the conclusion that he was mistaken. According to Pushkin, instead of an arrogant despot and tyrant, he saw a man “chivalrously beautiful, majestically calm, with a noble face.”

Personal Censor

After the Chudov Palace, a kind of “spiritual revolution” took place in Pushkin. The relationship has become more benevolent. The Emperor appointed Count Alexander Khristoforovich Benckendorf, the chief of the gendarmes and the head of the III department, as an intermediary between himself and the poet. It was to him that Alexander Sergeyevich had to turn in all cases.

In 1831, at the request of Pushkin, Nicholas I enlisted him for public service in the College of Foreign Affairs. Pushkin was given a salary of 5,000 rubles, and his salary was paid not from the financial funds of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but from the special fund of Nicholas I in the Ministry of Finance.

The patronizing attitude of the autocrat to Pushkin was also manifested in the fact that he declared himself the poet’s personal censor. It became a truly royal gift. Firstly, it significantly improved the creative and publishing capabilities of Alexander Sergeevich, and secondly, he gained access to the archives to write the “History of Peter” and the historical work about the Pugachev rebellion. True, the censored writer Pushkin also assumed certain obligations. He was not supposed to participate in any secret societies and fulfilled many personal requests of the emperor.

Last sorry

The year 1837 was tragic for Pushkin. On January 27 (February 8), Pushkin’s fatal duel with Dantes took place, two days later the poet died. Before his death, Nikolai Pavlovich and Alexander Sergeevich exchanged letters. Pushkin apologized for violating the imperial ban on participation in duels. And he asked his friend, poet and educator of the tsar’s children Vasily Zhukovsky: “Tell the Sovereign that I am sorry to die; it would be all His. Tell him that I wish him a long, long reign, that I wish him happiness in his son, happiness in his Russia.” In his letter , Nicholas I replied: “If God does not tell us to be seen in this world already, I send you my forgiveness and my last advice to die a Christian. Don’t worry about your wife and children, I’ll take them into my own hands.”

Nicholas I was faithful to his last letter to the poet and supported the petition. The emperor forgave the debt to the state treasury in the amount of 43,333 rubles 33 kopecks, paid all his monetary obligations, which reached 100,000 rubles (at that time it was a huge amount of money). The family of the deceased received a pension in the amount of 5,000 rubles, which could be received until the widow of the poet Natalia Nikolaevna remarried. Pushkin’s sons received 1,500 rubles a year until the time when they were enrolled in the prestigious Page Corps. The daughters also received 1,500 rubles before marriage. In addition, the tsar bought out the shares of co–owners in the poet’s ancestral estates – Boldino and Mikhailovsky, which his sons received. Finally, Pushkin’s works were published at the state expense, and the proceeds from book sales were transferred to the family.